The Passion of the Christ in Early Art

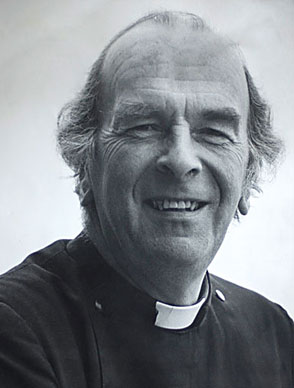

THE PASSION OF CHRIST IN EARLY CHRISTIAN ART The Very Rev A.C. Bridge

The Passion in early Christian art. May I first define what I mean by early Christian art; for I do not mean the art of those painters usually referred to as the Italian primitives - Cimabue, for instance - who painted in Florence and Siena and elsewhere in the latter half of the Thirteenth Century. They were not early Christian artists, but late. I’m talking about the artists of the late Roman world, who made some of the mosaics in the churches of Ravenna amongst other places, and those of the Byzantine world: that is to say, the painters, makers of mosaics and sculptors who lived and worked from about 350 AD onwards mostly in and for the Orthodox churches of Byzantium, but also occasionally in the West - for instance, in St Mark’s, Venice - and from whom such men as Duccio and Giotto took their inspiration. These were the early Christian artists.

Before then, for the first three centuries after the death of Christ, there was no Christian representational art at all, principally because it would have been regarded as idolatrous. Many of the early Christian Fathers were insistent, like the Jews before them, that all representatiye art was idolatrous. But it is also true that, when you are being persecuted for your faith, you don’t haye much time to paint the walls of the catacombs in which you meet secretly to worship. But after the adoption by Constantine in about 312 AD of the Christian faith as the offical religion of the Empire and the subsequent more or less mass-entry of the Greek world, with its passion for the arts, the old taboo against representative art began to disappear; though distrust of pictorial art was to recur again and again in the Semitic near East - in Syria, Iran and Egypt - where most people were Monophysite by conviction and hostile to their Orthodox brothers and sisters in Christ by a long-standing tradition of mutual misunderstanding; and, of course, even in the heart of Byzantine Orthodoxy, the old horror of idolatry was to triumph again during the Iconoclastic period in the Eighth and Ninth Centuries, when much genuinely early Christian art was destroyed, as it also was later when Eastern Christendom was dominated by the Ottoman Turks for 450 years. As a result, we have only a remnant left of the art of the first millenium of Christianity with which to judge it.

But even though it is only a remnant, there is enough to make one thing glaringly obyious: until the end of the period we are looking at - that is to say, until the Tenth and Eleventh centuries after Christ - the Passion - the Crucifixion - was virtually never represented; and even when it does occur, as in the Tenth Century Church of Hosios Loukas in Greece near Mount Phoeis and in the Eleventh Century Church of the Monastery at Daphni near Athens, it takes an entirely subsidiary place in the overall decoration. Whereas in many western Churches, the entire interior is dominated by a huge Crucifix over or behind the main altar at the east end of the church, early Orthodox churches are nearly always dominated by a huge mosaic of the risen Christ, the ruler of all things, Christos Pantocrator in a great conch over the apsidal east end of the church. In a few early churches - San Apollinare in Classe in Ravenna built in the Sixth Century and Hagia Irene - the church of the Holy Peace - in Istanbul built at much the same time, and recently beautifully restored by the Turks, there is a bare cross - a cross without a crucified figure on it - in the apsidal conch at the east end of the church; but for the Cross - let alone the Crucifixion - to be given such prominence is rare. Why? Why did the earliest Christians avoid representing the crucified Christ in their churches until so late in their history - and even then confine such representations to minor positions in their churches or to Icons for devotional use in their houses?

Part of the answer to that question - though only a small part, I suspect may be provided by a graffite etched on a wall in Rome. It is of a figure of a crucified man with an ass’s head, and it is inscribed with the words, “Alexemnos’s God. I don’t know its exact date, but it is early, and its message is abundantly clear; how on earth can anyone believe that the obscure execution of a common criminal in some remote part of the Roman Empire years ago can possibly have anything to do with God or the gods? What an astonishing - indeed, almost ludicrous - claim Alexemnos and his fellow Christians were making - or so it must have seemed to millions of people at the time, as indeed it has continued to seem to non-Christians ever since; a fact that we easily forget. For instance, on the 8th of July, 1099, when the men of the first Crusade were beseiging Jerusalem with very lttle success, they decided that their lack of progress must be due to God’s displeasure; plainly they were sinners; and so they marched barefoot around the walls of the city in a great procession of penitence to the huge amusement of their Moslem foes on the walls, who shrieked abuse at them and carried crosses on their backs in mockery, while their women flung dung at them. Nor have things changed much. Recently, a lady novelist accused Christianity of being a male-dominated cult centred upon a disgusting sado-masochistic obsession with blood and death, and a cannibalistic rite: that is to say, respectively the Crucifixion and the Eucharist; and while such an opinion is both a bit extreme and also obviously coloured by militant feminism, it is understandable. For when the world hears talk of God or the gods, most people assume that such talk is about beings with supreme power over mankind, not about a dead man in a position of total weakness, nailed to a Cross. Thus, the Cross will always remain a stumbling block to Jews and foolishness to Greeks, as St Paul knew; and it may be that Christians in Byzantine days decided that it would be a bad idea to emphasize that stumbling block visually in their churches, thus confronting visitors with its apparent foolishness in positions of great prominence, as was to become customary later in the West.

But however that may have been, it certainly wasn’t the principal reason for the absence of representations of the Crucifixion and the Passion in most Byzantine churches. To understand the real reason, you have to understand the nature of the real world as envisaged by virtually everyone, who worshipped in those churches. For us in the Twentieth Century, whether we are Christians or not, the real world is the world of shopping, making a living, educating our children, holidays in Spain, old age, arthritis and so on: in fact the world into which, eyen for most Christians, religion does not enter or enters once a week on Sundays and for ten minutes of prayer each night before we go to sleep. For the Byzantines - or to the vast majority of them - the real world was the next world: not this transitory world in which we spend troubled years; their primary citizenship was in heaven, their primary allegiance was to God through the risen Christ, and their daily lives were lived in the supernatural company of angels and archangels and all the company of heaven in the perspective of eternity. In other words, the real world was the world depicted by the mosaicists and the painters who recreated it visually in their churches: a world dominated - not by the Cross - but by the risen Christ, who occupies the highest point at the east end of the church, and towards whom everyone else represented is subordinate and must therefore face. He is Almighty, the Pantocrator, the ruler of all things. In the same position of honour in side-aisles or chapels, one may find representations of the Harrowing of Hell, with the the risen Christ pulling Adam and Eve and long-dead Prophets like Elijah by the hand from the realm of death to that of eternal life; there is a marvellus example in the Church of Christ in Cora in Istanbul; and sometimes you find representations of the Virgin - the Theotokos wth her divine child - in such positions. Meanwhile at lower levels appear angels and archangels, scenes from our Lord’s earthly life - the Transfiguration, the raising of Lazarus, the miracle of Cana of Galilee and so on - together with saints and martyrs and even a few bishops. This was the world in which the men and women of Byzantine days lived. They were intensely theological, rather than pious. For instance the Cappadoccian Father, Gregory of Nazianzus, writing to his mother in the late Fourth Century described how - and I’m quoting now - “If you go into a shop in Constantinople to buy a loaf of bread, the baker, instead of telling you the price, will argue that God the Father is greater than God the Son; the money-changer will talk about the Begotten and the Unbegotten instead of giving you your money; and if you want a bath, the bath-keeper assures you that the Son surely proceeds from nothing.” And this kind of thing was not unusual. The historian, Ammianus Marcellinus, recorded the fact that towards the end of the same Fourth Century, the Imperial transport system was so frequently distrupted by bands of Bishops travelling from Synod to Synod for doctrinal conferences that no one else could go anywhere. British Rail may have its faults, but being so clogged with peripatetic bishops that commuters cannot get to work is not one of them.

All this may or may not be of some historical interest, but has it anything relevant to say to Christians today? About the enormous primacy of the Resurrection - of the Risen Christ - yes, obviously, it has; for the Resurrection is central to the Christian faith. ‘If Christ be not raised,’ St Paul reminded the citizens of Corinth, ‘your faith is in vain.’ And so, of course is ours, if that be the case. But we all know that. So the early Christian visual emphasis in their churches upon the absolute supremacy of the risen Christ - the new Adam, the new creation, the pledge of both the faithfulness and the intention of God for us, should not surpise us. But what about the virtual absence of representations of the passion and death of Christ in their churches? Their relegation to visual obscurity? Do you know, I believe that it has even more to say to us than their visual insistanee upon the role played by the risen Christ in our self- understanding and in his place in Christian belief. For when you come to think about it, the Crucifixion - the culmination of Christ’s Passion - as an event in history is about as obscure as any event very well could be; the humiliating death of a man, utterly powerless to help himself. Now obscurity involves darkness; powerlessness and mockery invole weakness; and humiliation involves being despised by the world; but how often do we remember that it was only by passing through such obscurity, such darkness at noon, such weakness and mockery that our Lord was raised in power to become the Pantocrator? I don’t know the answer to that. Maybe some of us do indeed remember that the weakness of God is stronger than men, and the foolishness of God is wiser than men; but it doesn’t seem to me that corporately we do so very often. On the contrary, we look back with nostalgia to the various times in our history, when the Church was a power in the land, and strive to recreate them. Of course, we know that the medieval church had its faults, but at least everyone was Christian and went to Church, and how splendid that was! And what about the Victorian age, when our churches were full to overflowing? Wouldn’t it be good, we say to ourselves, if we could do as well today as our great grandfathers did a century ago. Those were the ages we really admire: the ages of power, and in our Stewardship Campaigns, our attempts to make our worship more popular, our distress at statistics of falling Church attendance, and even our Decades of Evangelism, we reveal our true aims. As in the economy, the business world, and the housing market we must aim to reverse the religious recession, to succeed, to expand. Corporately, the largely unquestioned criterion of our task as the Body of Christ is triumphalist. Or am I being unfair? Up to a point, I probably am.

Even so, think that we should be grateful to the artists of the early church, and to those who commissioned them to do what they did so superbly well, for reminding us visually that the true triumph of God often comes about through the obscurity and weakness of the Body of Christ - unnoticed, despised, accounted as foolishness - by the world; as has been demonstrated in our life time by the resurrection of the churches in Romania, Bulgaria, Czechoslovakia, Poland, and Russia after seventy years of suffering in obscurity and total weakness. To the Lenins and Stalins and Ceasars of this world Alexemnos’s God still has an ass’s head.

And at a less dramatic and nonetheless equally true level - and in strict conclusion - what about our own life as the Body of Christ - above all in the parishes? On every comic TV show, the Vicar is portrayed as a figure of fun - a bumbling ass - while his congregation is shown to be full of nit-wittcd old women and little else, while article after article in the press portrays the church as out of touch, irrelevant, and about to die. If so, it seems to me that it must be very like its Master and Lord. For when we are what the world calls weak, we are probably at our strongest in God’s eyes, and faith has always been accounted as foolishness by the worlds intelligent Greeks.