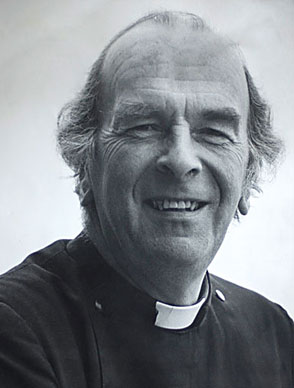

Tony Bridge: A light in the World

Taken from an Obituary published in the Marlburian Club magazine, Winter 2007

Until his late thirties Tony Bridge was a professional painter and an avowed atheist. His early commitment to atheism he attributed, characteristically, to sermons in the chapel at Marlborough. But as a result of his wartime experiences he underwent an intellectual conversion, which he described in a widely acclaimed book, One Man’s Advent (1985). His happiest, and perhaps most effective, period as a priest was when he was vicar of Christ Church at Lancaster Gate, Paddington.

His ministry touched the lives of countless people, not only through the parishes and the cathedral that he service, but also through radio and television and as chaplain and lecturer on Swan Hellenic Cruises. His preaching was legendary as a quote from a letter received by his widow, Diana, shortly before his funeral service testifies “When I was at Marlborough ‘A.C. Bridge’ came to take several Lent courses and he preached on a few occasions. Of all the preachers I had heard on leaving Marlborough he is the one who made the most impression. He inspired me. His attitude to Christian faith reached my teenage public school mind and set an example which has continued to influence me over 40 years later. Old Marlburians of my era, Christian or not, remember him vividly. He made an enormous impact for good on each of us”.

On first arriving at Lancaster Gate, Tony Bridge was appalled by the prevalence of prostitution and realised that he would have an enormous ministry of listening. But the bedsitter-land parish also contained many young professionals, and his style and sermons, which included such themes as the theological purpose of Picasso and Iris Murdoch, attracted a large congregation. With his highly personal yet intellectually rigorous exposition of the Christian faith he came to exert considerable influence during the 1960s.

Another letter to Diana says of Tony: “We were warmed by him, given fresh confidence, made to feel the world was a better place.” The kissing and embracing were for before and after the service; Tony was no great lover of the modern form of the Peace. Indeed when Series Two introduced it with the words ‘We are the Body of Christ’, the Bridge response, irreverent though sotto voce, was ‘Bully for you!’

Memorably he told the General Synod that to expect a committee to write a new liturgy was like asking the Board of British Rail to dance Swan Lake on Waterloo Station. What Tony did, as explained in this letter, “was to take the old forms and breathe fresh life into them; he turned water into wine. “Not I”, Tony might have said, “but Christ in me”. There was a kind of heady excitement about those Christ Church days. Tony wrote in his book Images of God that Cezanne was ‘moved to embody in pain his apprehension of something more than, beyond, and yet implicit in the materials spectacle of the landscape.’ In much the same way the congregation, made up of a kaleidoscopic range of people, were inspired by Tony to an apprehension of something more than, beyond, and yet implicit in the material spectacle of each other as God’s imagery and artistry. that was why people mattered and why love was paramount. Bayswater in the sixties, like fourth and fifth century Byzantium, was a-buzz with theology. It was partly the climate of the times, but largely because of an encourage between the holy Ghost and Tony Bridge in the Tottenham Court Road some years before. Everything was underpinned by much kindness, pastoral care, acceptance, encouragement, and hospitality at the Vicarage.

Although in many ways unconventional, Tony Bridge was in no sense a “trendy” clergyman; and he fiercely denounced many developments in the Church of England. He once accused it of transforming itself into :

“A bureaucratic annexe to the Welfare State with a few pious and neo-Gothic overtones. Hag-ridden by committees and worm-eaten by synodical government, it has dedicated itself to activism, having banished prayers, mystery, silence, beauty and its own rich musical and liturgical heritage to a few remote oases in order to make way for hymns written by third-rate disciples of Noel Coward and sung to the strident noise of guitars played by charismatic curates in jeans.”

Tony Bridge was spared most of this at Guildford Cathedral, but he was too much of an individualist to make a wholly successful Dean, and he had neither the inclination nor the aptitude to deal with the administrative and financial burdens which tend to dominate the decanal ministry. But he made good use of the cathedral pulpit, whenever he had a chance to occupy it.

Many were attracted to the cathedral by the intelligence of his preaching and the warmth of his personality. He was the first to admit that his talents did not extend far into the area of management, and he viewed his administrative duties with no enthusiasm; meetings of the cathedral chapter were introduced by “You poor sods don ’t want to be here and neither do I, so let’s get through with it”.

Held in great affection by many lay people who valued his humanity, kindliness and understanding, he did not go out of his way to endear himself to his fellow clergy, however. Arriving late at a crowded staff meeting in the bishop’s study he announce in loud tones: “My God, the stench of stale Christians.” Radical in many of his theological and moral views, not least on the subject of sex and marriage, he was deeply traditional in ways of worship and gave no encouragement to fashionable trendiness. Advocates of charismatic renewal his dismissed as “those silly buggers with guitars”. He was a brilliant maverick, and there were occasions when his sermons were received with a measure of consternation; he was at his most outrageous when confronted with a cathedral full of Surrey ladies in their best hats.

Tony was a big man not only in stature and presence, but big-hearted; in some ways larger than life. Perhaps, even, he was a great man. Samuel Becket, writing about the painter Jack B. Yeats, brother of poet W.B. said “He is one of the greats of our time, because he brings light as only the great bring light to the issueless predicament of existence.” By such a definition, Tony was also one of the greats of our time, a chosen vessel of God’s grace and a light of the world in our generation.